What does it mean to be a scientist?

I've known for a while now that a scientist is what I will

be--what I've been slaving over books late into the night to become.

But still the question remains: what does it mean to be a scientist?

It was a Wednesday afternoon, my observational astronomy professor,

Dr. Dale Gary, came into our rooftop classroom casual and cool like usual,

holding some papers, notebooks, and a few wires and filters for the telescope.

This afternoon, although seemingly average, was a touch different--nothing

completely bizarre or out of the ordinary, just that instead of starting

class off talking about the coming night's astronomy project,

Professor Gary casually mentioned an internship with NASA,

if any of us were interested...

I quickly came to my senses out of whatever daydream I may've been having:

the professor had my full attention. Ever since I had become an astrophysics major,

those around me have been completely confused as to what I'm going to do with

such a major. Some people would ask, "So, umm, you’re into horoscopes and

stuff?" To which I'd have to explain the difference between astronomy and astrology.

The more intelligent people around me, who kind of had an idea of what astrophysics

might be, would ask, "So, you plan on working for NASA or something?"

Good question.

Of course I had thought about it. Working for NASA was definitely on my list of

things to do...eventually. I mean--I didn't dream that it was any time in the near future:

I have my undergraduate degree to attain, never mind another five years afterwards for

my doctorate. But here was the opportunity staring me in the face.

"I'm going to work for NASA!" I thought. "Maybe I'll finally figure out what all these years of

schooling, months of solitude, days

devoid of sleep, and hours saturated with books have been good for." To my dismay, just as quickly as the professor brought the subject up, he abandoned

it for the night's lecture.

What we did that night, whether it was observing Saturn's moons or mapping out the

trajectory of an asteroid, I couldn't tell you. All I know is that my pulse was quicker

than usual, my awareness higher, and that my mind was racing with the excitement that

comes along with opportunity. I couldn't stop thinking about this internship. After

the class ended, I approached the professor to let him know that I was very, very

interested. He said he would email me the pertinent information and application requirements...

Doubt? Surely I would be lying if I told you I thought that I would actually get this

internship. Yea, I was determined to try my hardest--write up a really good résumé,

concoct a creative cover letter, make sure to get my two letters of recommendation

in--but I didn't honestly think for more than a few brief seconds at a time that I would

land this internship. I just thought it couldn't hurt to try.

The wait--nerves on end, insecurity rising--began after I pressed the "send" button, emailing the

intern coordinator, Ana Rosas, my 'credentials' (a few pages that basically begged for

a job, "I'm your man--c'mon, you gotta believe me!"). It didn't take long for the response

to come back: "Hi Kevin, the application deadline is over...." Lump in my throat. Pit in my stomach. I read the line again: "The application deadline

is over..."

#$*%!

"Well, there goes that," I thought. A moment of misery passed before I finally realized,

"Wait a second!" I read the entire email this time. The second sentence clearly stated,

"But you may still submit."

What? I could still get this thing. Sweet!

I decided I couldn't wait around hoping someone would peruse my résumé and--maybe--like

it enough to get in touch with me. I began emailing research scientists at NASA's Goddard

Space Flight Center asking each if they would accept me as an intern. To my elation, most

emailed me back. Unfortunately, I never found the "Yes!" I was looking for--just a longwinded

'Nope,' 'Not really,' or plain old 'No', time and again.

"Well, at least I gave it my all," I told myself. I emailed Ana Rosas once more, asking

if anything opened up. Nothing. Darn. So, that was that, I gave up on the idea. After all the hype and excitement, I wasn't

going to be working for NASA.

Or so I thought.

It was the last week of school before finals began--I was on the phone with a buddy of mine,

telling him I was planning on moving in for the summer when I got the call:

Ana: "Hello, is this Kevin Urban?"

Kevin: "Yes, it is."

Ana: "Hi. This is Ana Rosas, are you still interested in working for NASA?"

I think it is obvious how I responded.

Working at NASA

Ana: "You'll be using some PHP, which Dr. Thompson said you can learn when you get down

here. But you definitely ought to know HTML..." I didn't respond. "Do you know it?"

Uh-oh.

Panic sirens began screeching in my head. The only two things I knew about HTML were making

links and putting up images. Pretty much nothing!

Kevin: "Umm, yea--taught myself everything I know..."

finishing the sentence in my head,

'...nothing.' (gulp)

The next few seconds were dizzying. I suddenly wasn't sure if I was going to get the

internship or not.... It was the longest moment I've ever known.

"Wihoo!" I shouted, jumping in the air and clicking my heels. "I landed the internship!"

When the rush wore off, I realized I didn't know anything about PHP or HTML.

"Better get to work," I thought.

I had two weeks--and I didn't waste any time. For eight hours a day, five days a week, I drilled

myself in HTML coding, finding it easy to master. I moved on to an extension language to HTML known

as Cascading Style Sheets (CSS), and even began teaching myself a little bit of javascript before I

left for Maryland.

When the day came to leave, I said my goodbyes to family and friends. I couldn't help but to

feel like a boy setting off to become a man. As I drove off, I waved my hand out the car window

in mock-slow motion, trying to be dramatic as possible as my brother faded into the distance.

He played along quite well and called out, "Go get 'em, kid!"

When I arrived at NASA I didn't know what to expect. I basically knew my job was going to

consist of computer programming, something that two weeks ago I had no experience with, and

that I was working for a project called the International Heliophysical Year (IHY). That's it.

Other than that, I was hoping my 'mentor' (that's what we call our supervisors) didn't expect

too much of me.

I guess you can say...she did.

I remember with clarity not understanding a word she said. "Could you create for the IHY website

an intelligent search tool that will..." I wiped the sweat from my brow and thought, 'Kevin, you

really got yourself in a mess this time.'

I meticulously searched Google for key terms I heard her say, such as "content management

system," "search tool," and "freeware." Although I began learning more and more about these

computer-related topics, I still was in the dark as to what I was to do with any of this

knowledge... When all hope seemed lost, Dr. Thompson casually mentioned that a web content

management system called "Plone" might be useful to me, but she wasn't all too sure and just

left it at that. Plone was to be the answer I was looking for and the bane of my first month and a half.

You see, Plone offered, to those who were equipped with the skill to use it, everything that

Dr. Thompson was looking for, specifically intelligent website/database search capabilities.

It is considered to be one of the best web content management systems available. The more

I read about it, the more I knew: this is what I need to complete the task I was given.

One little problem stood in my way: I was not equipped with the skill to use it.

To make matters worse, I found that Plone was built on a "web application server" (another

term I had no clue about) called "Zope," which was built using the freeware programming language

called "Python." Questions plagued my mind: What exactly is Plone? How do I use it? Do I need

to install something? Do I need to learn Zope or Python to be able to use Plone?

"Oh, I just want to go home and start over again tomorrow," I thought.

Home. I almost forgot to mention it--the place where some of my fondest intern memories were made.I knew I wasn't going to commute from New Jersey to Maryland everyday--that's just plain

ridiculous. So I had to come up with a place to live: somewhere nice, somewhere close,

somewhere cheap! Living alone was out of the question when I saw that it'd cost me $800+ per

month. "Maybe I can find some roommates," I thought.

I remembered receiving a list of emails of the other interns, so I decided to send out one big,

mass email asking if anyone was interested in--maybe--renting a house. That same day I also received

an email from another intern, Robert Niffenegger, looking for some possible housemates too.

Robert, who I came to know as Bob, checked Craig's List (an internet classifieds webpage) for

houses located near the Goddard Space Flight Center. A few emails back and forth, a few to some

other interns, some help from the intern coordinator, and--BAM!--Bob and I had ourselves a house

with three other interns.

The best advice I can give about an internship with NASA--nay, any internship--is this: if you get

the chance to rent a house with a bunch of other interns, do it! J.D., the main character from my

favorite TV show, "Scrubs," a sitcom based around the lives of hospital interns, once said:

"I challenge anyone to survive as an intern without a close group of friends to lean on." Yea,

I'm sure it's possible to get on without a close group of friends, but there's nothing like

sitting around a dinner table with people who all share a common interest:

"Recent research suggests that quantum teleportation may some day be a possibility."

"Yea, and those researching quantum dot technology claim that the possibility of invisibility

ain't far off either!"

"Sweet."

"Definitely. Pass the mashed potatoes."

Sometimes, as an intern, work can become overwhelming--a problem with your programming code,

an equation you can't figure out, a machine you need to use isn't working. I can't imagine having

to go home to a lonely apartment after a long, stressful day and having nothing to do but to wait

for tomorrow. Living with other interns, it was impossible to mope in loneliness and self-defeating

thoughts--there was never a moment we weren't doing something, making it hard to stay stressed for

too long. We cooked dinner for each other, played video games together, watched every single

episode of "Scrubs." Some nights we would all go out to play tennis, others we would go downtown to D.C. for the night.

We even were able to host a few parties at our house, which we called "the NASA House"

and joked that our fraternity name was Nu Alpha Sigma.

Living with four other interns also gave me the opportunity to observe their daily progress,

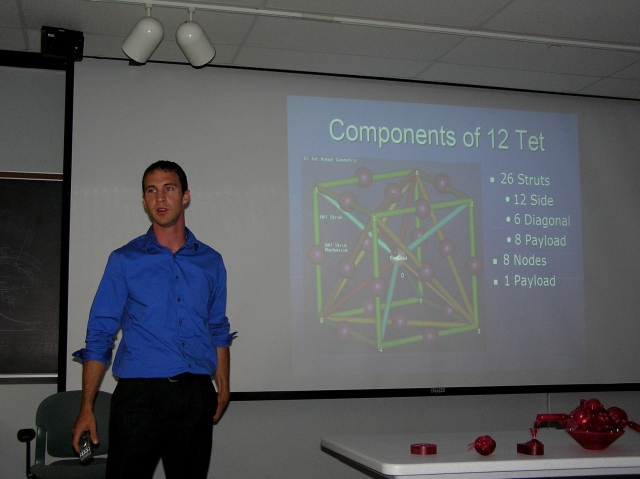

to witness them grow as scientists. Derrick  , 23, a mechanical engineering major, worked on a

robot called the "12-tet" that will eventually scale the terrain of Mars;

Colleen

, 23, a mechanical engineering major, worked on a

robot called the "12-tet" that will eventually scale the terrain of Mars;

Colleen  , 21, an

astrophysics major, created an interface between a telescope and computer in the programming

language IDL for GISMO, a project that when completed will allow astronomers to observe galaxies

further away than anything yet possible; Bob

, 21, an

astrophysics major, created an interface between a telescope and computer in the programming

language IDL for GISMO, a project that when completed will allow astronomers to observe galaxies

further away than anything yet possible; Bob  , 19, a physics major, developed a program that

simulates the thermo-momentum of the surface layer of the moons of Saturn; and

Dan

, 19, a physics major, developed a program that

simulates the thermo-momentum of the surface layer of the moons of Saturn; and

Dan  , 22,

a physicist turned mechanical engineer, contributed to designing/researching microshutters

for the James Webb Space Telescope, which will allow multiple objects to be observed at one

time by the telescope, therefore increasing the amount of data that can be collected per unit time.

, 22,

a physicist turned mechanical engineer, contributed to designing/researching microshutters

for the James Webb Space Telescope, which will allow multiple objects to be observed at one

time by the telescope, therefore increasing the amount of data that can be collected per unit time.

Outside of the house, back at NASA, I met scientists and engineers daily who worked on

such renowned projects as the Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), the Solar and Heliospheric

Observatory (SOHO), the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO), and the Reuven

Ramaty High Energy Solar Spectroscopic Imager (RHESSI). I was able to talk with these successful

people, ask them questions, and sometimes even swap emails. Moreover, every Wednesday, a research

scientist would do a lecture for the interns with topics ranging from solar storms to society's

effects on the ozone layer to magnetic fields. This gave interns the opportunity to see what else

is going on at NASA outside of their own little niche, and put names to faces of scientists who

have impacted science, technology, and society.

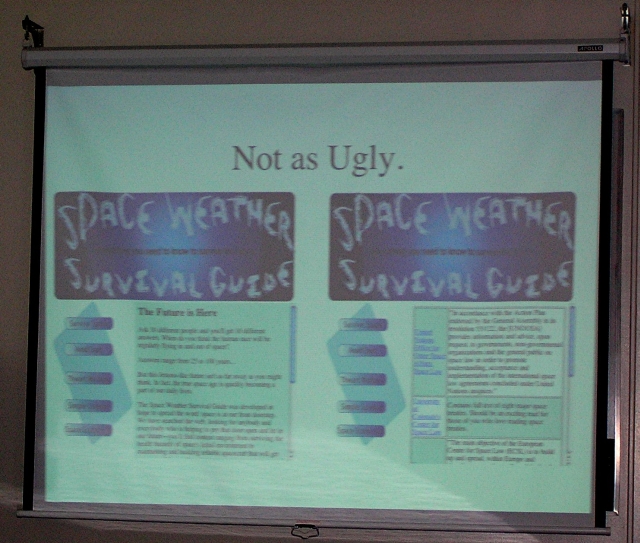

While interning at NASA, I learned a lot about the Sun and its effects on Earth--about space

weather. One task I was given was to create a website that can relate to the non-specialist

everything one needs to know to survive the upcoming space age--the true space age where the common

man will successfully inhabit the vacuum of space, where trips to the moon will be routine, and

the idea of visiting mars will be a question of vacation location--not science. The website, which

I call the Space Weather Survival Guide, can be found at www.spacesurvival.org. It's not much,

I'll admit, but just know that behind every line of code, every graphic I designed, was a day

filled with fun, friends, and--especially--a few cups of coffee.

Sitting here, writing this, reflecting on my summer at NASA, I cannot think of one bad memory.

In a single summer, I feel I've accumulated a lifetime of experiences: I learned to play tennis,

went whitewater rafting, joined an acting class. I learned the computer programming language Python,

the basics of using a Unix shell, the intricacies of designing a website. I traveled to D.C. on

a regular basis, visited Annapolis, saw the bay of Baltimore. I went to baseball games, a concert,

checked out the local scene. Most importantly, I made friends who I will never forget, and I got to share these

experiences with them. Intellectually I've grown, emotionally I've matured. I came to NASA unsure

of myself, but tomorrow I will be leaving, knowing full well that I have an incredible future

ahead of me, being a scientist.

Finding a Home at NASA

Finding a Home at NASA

Finding a Home at NASA

Finding a Home at NASA